Data engineering: the invisible backbone of digital

Behind every digital application lie data infrastructures that collect, transform, and make information …

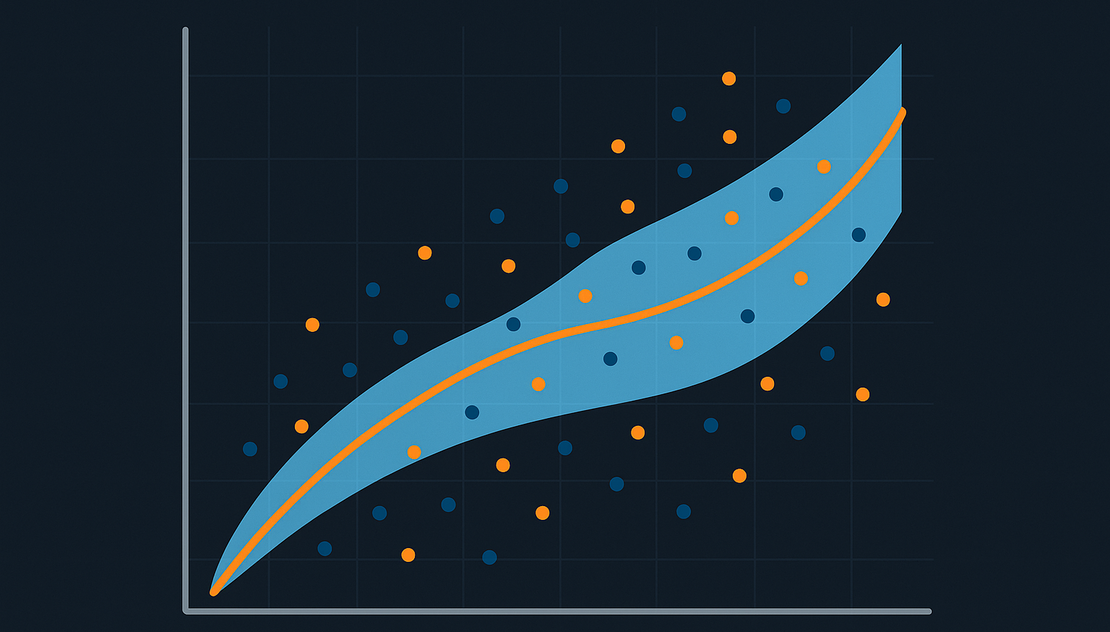

Machine Learning is increasingly used in business and in the management of complex systems such as energy, finance, or healthcare. Yet there is one element that is often overlooked: the uncertainty of predictions.

A model may seem accurate, but without a measure of confidence in its estimates, it risks turning into a black box that is of little use, if not downright dangerous.

Imagine you want to predict whether it will rain tomorrow. You can check the weather forecast, but you will never have absolute certainty: meteorologists express the forecast in terms of probability (“60% chance of rain”).

This probability represents uncertainty: we do not know exactly what will happen, but we can estimate how much we should trust the forecast.

The same is true for Machine Learning models. Every prediction carries a margin of uncertainty. This uncertainty has a dual nature: on one hand, the intrinsic unpredictability of the phenomenon being measured (like rolling a die), on the other, the limitations of our model, linked to the quantity or quality of the data it was trained on. Ignoring these factors means deluding ourselves into thinking we have exact answers in a world that remains, by nature, partially unpredictable.

A model that provides only a “dry” number is not enough to make business decisions. We also need to know how much we can trust that number.

Let’s take a concrete example in the energy sector: the management of a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS).

An operator may decide to charge the batteries when electricity is cheap and discharge them when the price rises, thus maximizing profit.

If the model predicts that tomorrow the price will rise by 20%, without a confidence interval we do not know whether this estimate is reliable or whether there is a high risk of error. A well-designed model should instead say:

Our model predicts a 20% price increase, and we are 90% confident that the actual increase will be between 15% and 25%.

With this information, the operator can assess risk, choose more cautious or diversified strategies, and make informed decisions. Without a measure of uncertainty, the model would not be usable in practice.

Having an estimate of uncertainty is not enough: that estimate also needs to be calibrated.

A calibrated model is one in which the stated probability actually corresponds to the real frequency.

Let’s go back to the BESS example:

if the model says there is an 80% chance the price will rise, then out of 100 similar cases we expect the price to rise in about 80 of them.

If this does not happen — for example, if the price rises only in 40 out of 100 cases — then the model is not calibrated and its uncertainty becomes misleading.

Calibration, therefore, is what turns prediction into a truly useful tool: not just a number, but reliable information with which to make decisions.

In recent years, Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown impressive capabilities in generating text, code, and complex answers. However, when it comes to making critical decisions, they present a fundamental limitation: they struggle to express their uncertainty in a reliable way.

LLMs often provide answers with a tone of confidence even when their reliability is low. Moreover, correctly calibrating their “confidence” is much harder than with traditional predictive models. This makes them unsuitable for contexts where we must rely on measurable and responsible predictions, such as energy management or healthcare.

In Machine Learning, there are several approaches to estimate uncertainty:

For calibration, the most widely used methods are:

A particularly interesting approach is Conformal Prediction (CP):

In the BESS example, instead of simply estimating +20% ± 5%, CP might say: with 90% confidence, the price will vary between +15% and +25%.

Every Machine Learning prediction must be accompanied by a measure of uncertainty: without this information we cannot trust the model, nor can we use it in business scenarios, let alone in critical contexts.

Calibration is what ensures that uncertainty estimates are realistic and usable.

The final message is clear: the value of Machine Learning lies not only in the accuracy of the prediction but also in the transparency with which it communicates its limits.

Only in this way can we build reliable, responsible, and sustainable solutions capable of generating real benefits for companies, citizens, and society.

Behind every digital application lie data infrastructures that collect, transform, and make information …

Batteries reaching the end of their life are not necessarily waste: they can open new market opportunities and …